« Processes, Benefits, and Applications in Modern Industry »

Work hardening occurs when metallic materials are deformed below their recrystallization temperature. Discover how mechanical properties of metals change during forming processes, which industries benefit from increased material strength, and the additional hardening methods used in various manufacturing processes.

Cold Forming

Cold forming is ideal for mass production due to its ability to achieve high material throughput in a short amount of time. Additional advantages include material integrity, efficient material utilization, and relatively low energy consumption. Metals can be shaped into almost any form using intense mechanical forces. These new contours are created with tools that shape the material according to design specifications.

Despite the high processing speeds, pressures, and temperature increases used in the process, forming lubricants ensure that tools maintain a cost-effective lifespan. Kluthe offers a wide range of friction-reducing products, including Hakuform, Hakuforge, and carrier coatings like Decorrdal zinc phosphating, which are specifically adapted to different manufacturing conditions.

Work Hardening

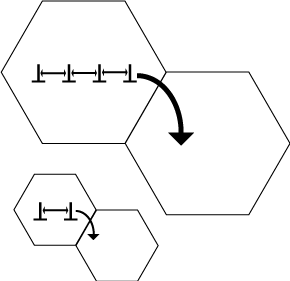

A key side effect of cold forming is work hardening, which enhances the mechanical properties of manufactured components, allowing them to withstand high operational loads. In most manufacturing processes, increasing material strength is a desired outcome, especially in cold rolling, tube drawing, wire drawing, and other bulk cold forming techniques.

The benefits of work hardening can be seen in everyday American products, from the stronger aluminum used in MacBook laptop bodies, to the durable stainless steel in kitchen appliances like KitchenAid mixers, and even the paperclips on your desk. However, in some cases, increased strength can hinder further processing. When needed, the material can be annealed (recrystallized) to restore its original mechanical properties. This step is essential when multiple forming stages are required to achieve the final shape, such as in multi-stage drawn tubes, cold-headed parts made from drawn wire, or bulk cold-formed components. Intermediate annealing helps regain the necessary material properties.

Metal Deformability and Crystal Structure

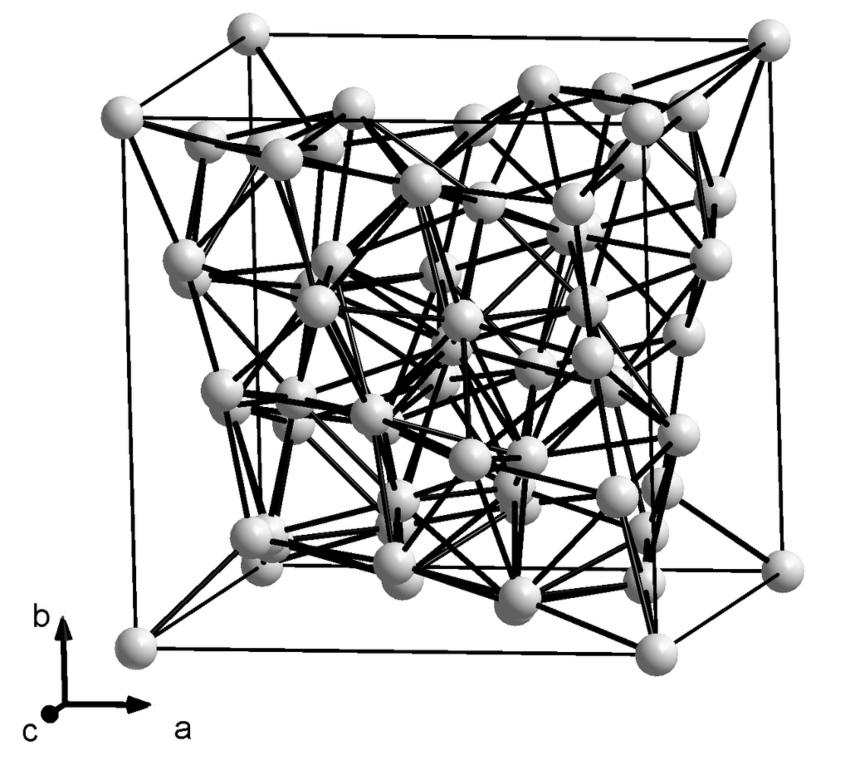

Lattice Structure

The deformability of metals can be attributed to their crystal structure. As the melt solidifies, particles (atoms, ions) initially arrange themselves at randomly distributed locations to form regularly structured crystal lattices. While the melt becomes solid, more and more particles attach to the lattice (crystal growth). Occasionally, irregularities occur, which in materials science are referred to as lattice defects. Simple defects include:

- Foreign atoms – take the place of a particle and distort the lattice due to their different size.

- Vacancies – individual particles are missing in the lattice.

- Interstitial atoms – additionally embedded in the lattice.

Dislocations in the Lattice

Dislocations in the crystal lattices significantly influence material behavior during cold forming. Materials science distinguishes between edge dislocations and screw dislocations. Edge dislocations occur due to the addition of half-planes within a crystal, causing neighboring planes, which normally run parallel, to deviate sideways. Planes running perpendicular to the half-plane maintain their position. Screw dislocations, on the other hand, occur when lattice regions assume an oblique course to bridge missing components, forming a spiral pattern throughout the crystal lattice.

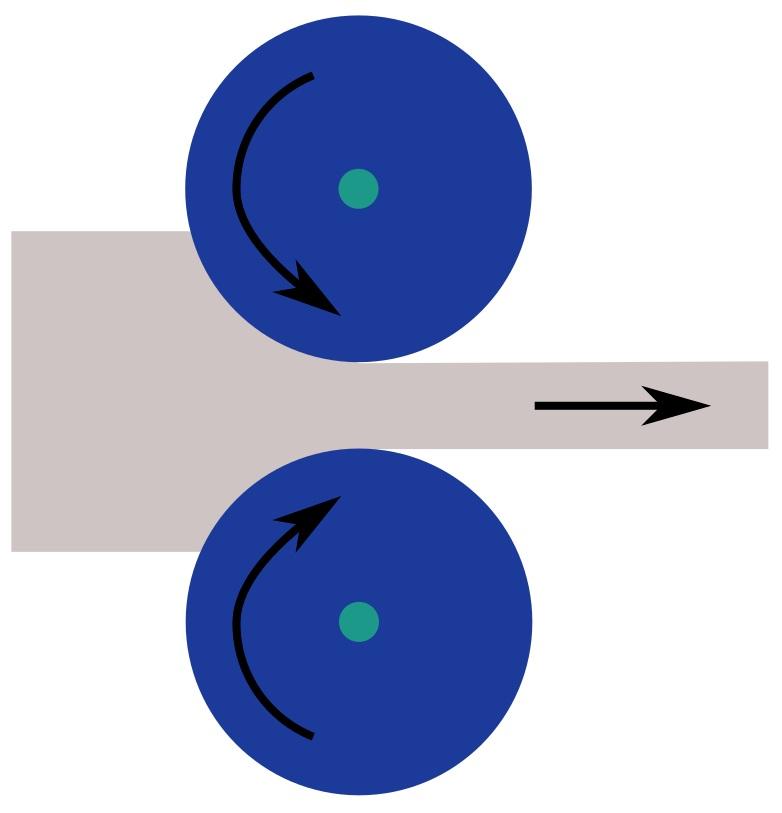

Influence of Dislocations on Cold Forming

Dislocations weaken atomic bonds, allowing materials to deform. When external forces are applied, dislocations move through the lattice, enabling the metal to take its intended shape. However, as new dislocations accumulate, they begin to interfere with each other, increasing resistance to further deformation. This effect, known as work hardening, gradually strengthens the material.

Recrystallization

Lattice structures are in constant motion, vibrating around their ideal positions, a motion directly correlated with temperature. When the temperature surpasses a critical threshold, the thermal energy allows atomic rearrangement, eliminating many dislocations and restoring the lattice. This temperature is known as the recrystallization temperature, typically around 40-50% of a material’s absolute melting temperature. Some metals, such as zinc (787°F / 418°C), lead (622°F / 328°C), and tin (450°F / 232°C), cannot undergo work hardening because their structures automatically realign after deformation.

Additional Hardening Methods

Grain Refinement

As molten metal solidifies, its crystal grains grow until they meet neighboring grains, forming grain boundaries. Since adjacent grains have different lattice orientations, grain boundaries resist deformation, increasing material strength. Grain refinement enhances strength by controlling cooling rates and introducing crystallization nuclei, increasing the number of grain formation sites. The result is a finer grain structure with more grain boundaries, boosting strength while preserving toughness—unlike work hardening, which increases brittleness.

Precipitation Hardening

Most metals used in industry are alloys, composed of multiple chemical elements. For example, steel is an alloy of iron and carbon, with additional elements enhancing corrosion resistance and mechanical properties. Since different elements exhibit varying solubility in metal lattices, precipitation hardening involves heating the alloy to dissolve alloying elements uniformly, followed by rapid quenching. This process creates supersaturated crystals containing more foreign atoms than the lattice can accommodate. Over time, excess atoms migrate out of the lattice, forming precipitates at grain boundaries, restricting dislocation movement, and increasing strength.

Solid Solution Hardening

Most pure metals are too soft for industrial applications. Alloying elements can be introduced to increase strength by occupying lattice positions (substitutional hardening) or embedding between lattice atoms (interstitial hardening). These additional elements distort the lattice, making it harder for dislocations to move.

Industrial Applications for Work Hardening

Work hardening plays a crucial role in many cold forming processes, improving the mechanical properties of manufactured parts. Modern forming simulations allow precise control of work hardening levels, optimizing manufacturing processes for specific performance requirements.

This effect is particularly beneficial in bulk cold forming, where components such as transmission parts for Ford F-150 trucks, aerospace fasteners for Boeing aircraft, and high-load components in American automotive and defense industries are produced in large volumes within short cycles. Work hardening also benefits wires, tubes, and structural profiles used in construction and steel fabrication.

Work hardening processes have been central to manufacturing in America’s industrial heartland, from Steel Belt manufacturers to aerospace suppliers in Washington state and automotive parts makers in the Southeast. These advanced metallurgical techniques support over 500,000 American manufacturing jobs and contribute significantly to the $2.3 trillion U.S. manufacturing sector.

Kluthe Magazine

Kluthe Magazine