The flash point is a fundamental safety parameter used to assess the hazards associated with flammable liquids. In surface treatment and processing, cleaning agents, solvents, paints, coatings, and lubricants are widely used — and many of them are flammable. Measures to prevent fires and explosions are based on the flash point and additional safety-related parameters.

The Flash Point – A Simple Definition

The flash point is the lowest temperature at which vapors released by a flammable liquid under standard conditions can be ignited. Standard conditions correspond to a temperature of 70 °F (21 °C) and an average atmospheric pressure of 14.5 psi (1 bar). As the liquid warms, evaporation increases and more vapor is released. Once the boiling point is reached, the liquid begins to vaporize rapidly. The physical property that describes this behavior is vapor pressure, which is determined by lowering the air pressure above a liquid at constant temperature until it begins to boil.

Vapor Pressure and Explosion Limits

In a closed vessel at constant temperature, an equilibrium develops between the vapors in the air and the liquid. The concentration of vapor in the air corresponds to the ratio of vapor pressure to total pressure. If this concentration falls within the explosive range, the mixture can be ignited; outside this range, there is either too little or too much vapor for ignition to occur. The lower and upper explosion limits are, like the flash point, safety-related parameters. Unlike intrinsic physical properties, they depend on the test conditions under which they are measured. To ensure comparable results, these conditions are standardized according to ASTM and ISO test procedures (for example, ASTM D92, ASTM D93, and their ISO equivalents).

Determining the Flash Point

To determine the flash point, the flammable liquid is slowly and evenly heated in a standardized test apparatus. At regular temperature intervals, an ignition source is activated, until the flash point is reached, the vapor ignites briefly, then quickly extinguishes because the liquid cannot yet supply sufficient vapor to sustain combustion. If heating continues, a stable flame forms once the rate of vapor generation equals the rate of combustion. The temperature at which this occurs is called the fire point, which typically lies close to the flash point. For safety assessments, the fire point is of secondary importance.

Importance of the Flash Point in Hazard Assessment

The flash point is the basis for assessing the flammability of liquids. Classification systems vary by region. In the United States, OSHA and NFPA define the following classes for flammable and combustible liquids: Class IA liquids have a flash point below 73 °F (23 °C) and a boiling point below 100 °F (38 °C). Class IB liquids have a flash point below 73 °F (23 °C) and a boiling point at or above 100 °F (38 °C). Class IC liquids have a flash point at or above 73 °F (23 °C) and below 100 °F (38 °C). Class II liquids have a flash point at or above 100 °F (38 °C) and below 140 °F (60 °C). Class IIIA liquids have a flash point at or above 140 °F (60 °C) and below 200 °F (93 °C). European classification systems use slightly different thresholds: liquids are considered highly flammable below 32 °F (0 °C), easily flammable between 32 °F (0 °C) and 70 °F (21 °C), and flammable between 70 °F (21 °C) and 131 °F (55 °C).

Explosion Protection Measures

When handling highly or easily flammable liquids, explosion protection is mandatory. Vapors from these liquids can form explosive atmospheres that can be ignited by a single electrical spark or a spark caused by mechanical impact. In such an atmosphere, flames can propagate at speeds exceeding 330 ft/s (100 m/s), causing a rapid rise in pressure and temperature that further accelerates combustion.

Flammable liquids may also ignite on friction-heated surfaces once the material’s specific ignition temperature is reached — regardless of the flash point. Even a localized temperature increase can be sufficient to trigger a fire. Hazard assessments also consider water miscibility. Fires involving water-miscible liquids can usually be extinguished with water, whereas those involving non-miscible liquids require special extinguishing methods.

Flammable Liquids in Surface Processing

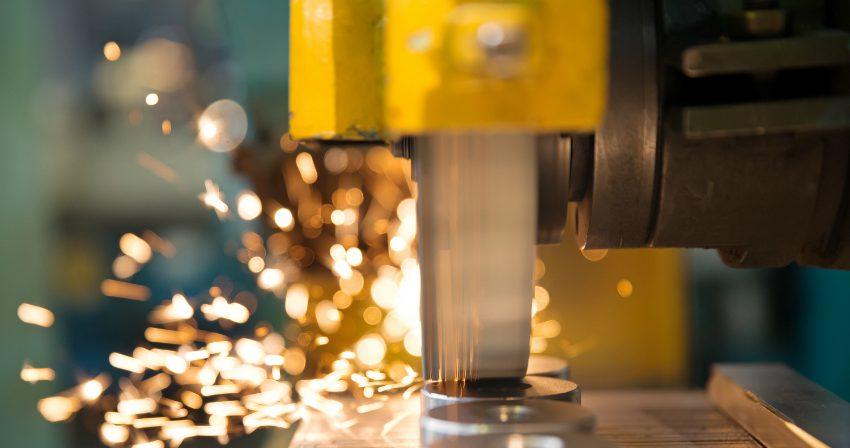

In mechanical surface processing, flammable liquids are used as non-water-miscible cooling and forming lubricants, as well as in concentrates for water-miscible coolants.

Cooling Lubricants

Mineral oils with flash points above 212 °F (100 °C) are commonly used as cooling lubricants. Technically, they are not classified as flammable liquids, yet they can still burn when heated to their ignition temperature. Even small additions of easily flammable substances — such as solvents or water-displacing agents from parts cleaning — can significantly lower the flash point. If the cooling effect is reduced due to suboptimal process conditions or equipment malfunction, a fire could occur.

Forming Lubricants

Processes such as rolling and deep drawing use forming lubricants that, for technological reasons, often have flash points only slightly above 131 °F (55 °C). Their necessary flowability comes at the expense of reduced safety. Since elevated temperatures occur in these processes, areas at immediate risk must be designated as hazardous locations (Class I, Division 1 or 2 per NEC) where ignition sources are strictly prohibited.

Flammable Liquids in Surface Treatment

In surface treatment, flammable liquids are often used both for cleaning parts and for applying paints and coatings.

Industrial Cleaners

Before surface treatment, parts are usually thoroughly degreased. Most industrial degreasers are highly flammable liquids, such as denatured alcohol or petroleum ether. Vapors produced during cleaning can form ignitable mixtures with the air. If alternative cleaning methods cannot be used for technical reasons, appropriate safety precautions must be taken.

Paints and Coatings

Solvent-based paints and coatings dry faster than waterborne versions and therefore remain widely used. Local exhaust ventilation (LEV) prevents vapors from accumulating and spreading in the workspace. With suitable recovery systems, the solvents can also be reclaimed for reuse.

Explosion Protection in Industry

Industry applies several levels of explosion protection, prioritizing preventive measures that stop explosive atmospheres from forming in the first place.

- Highly flammable substances should be replaced, whenever possible, with materials having a higher flash point, or processed and stored in sealed systems and containers. This approach is known as primary explosion protection.

- Measures that prevent the ignition of explosive mixtures are part of secondary explosion protection, which is particularly important in the design of electrical systems and the classification of hazardous areas.

- If the risk of explosion cannot be eliminated, tertiary explosion protection methods are required to limit potential effects. These include pressure relief devices and explosion suppression systems.

Conclusion for Surface Processing and Treatment

Before using any chemical substances in the surface processing industry, it is essential to determine whether they pose a fire or explosion risk. Critical safety information can be found on product packaging or labels, often indicated by standardized GHS hazard symbols. Safety Data Sheets (SDS) — structured under the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) and implemented through OSHA’s Hazard Communication Standard (HCS) in the U.S. and REACH in Europe — provide detailed information on these parameters. Section 9 lists the physical and chemical properties, including the flash point where applicable.

Kluthe Magazine

Kluthe Magazine