Anodizing is the term for electrochemical processes in surface technology that create mechanically and chemically stable oxide layers on suitable metals. The word “anodizing” corresponds to the German term *Eloxieren*, derived from the initial letters of “elektrochemisch” and “Oxid.” Here you can learn about the process sequence, the areas of application for anodizing, and the natural laws at work in the process.

A Brief Insight into Electrochemistry

Join us for a short excursion into electrochemistry to better understand the fundamentals that make this process so important in surface technology.

Energy Source

Electrochemistry typically uses direct current sources for anodic oxidation. These are characterized by a positive and a negative terminal. At the negative terminal, an excess of negatively charged electrons is present. Nature tends to equalize this charge difference (also known as electrical voltage or potential difference). Humans have learned to route this equalization through lamps, motors, or heating elements to obtain light, mechanical energy, or heat. Nature has also made it possible to use charge equalization in surface technology: through electrochemical reactions.

Electrodes

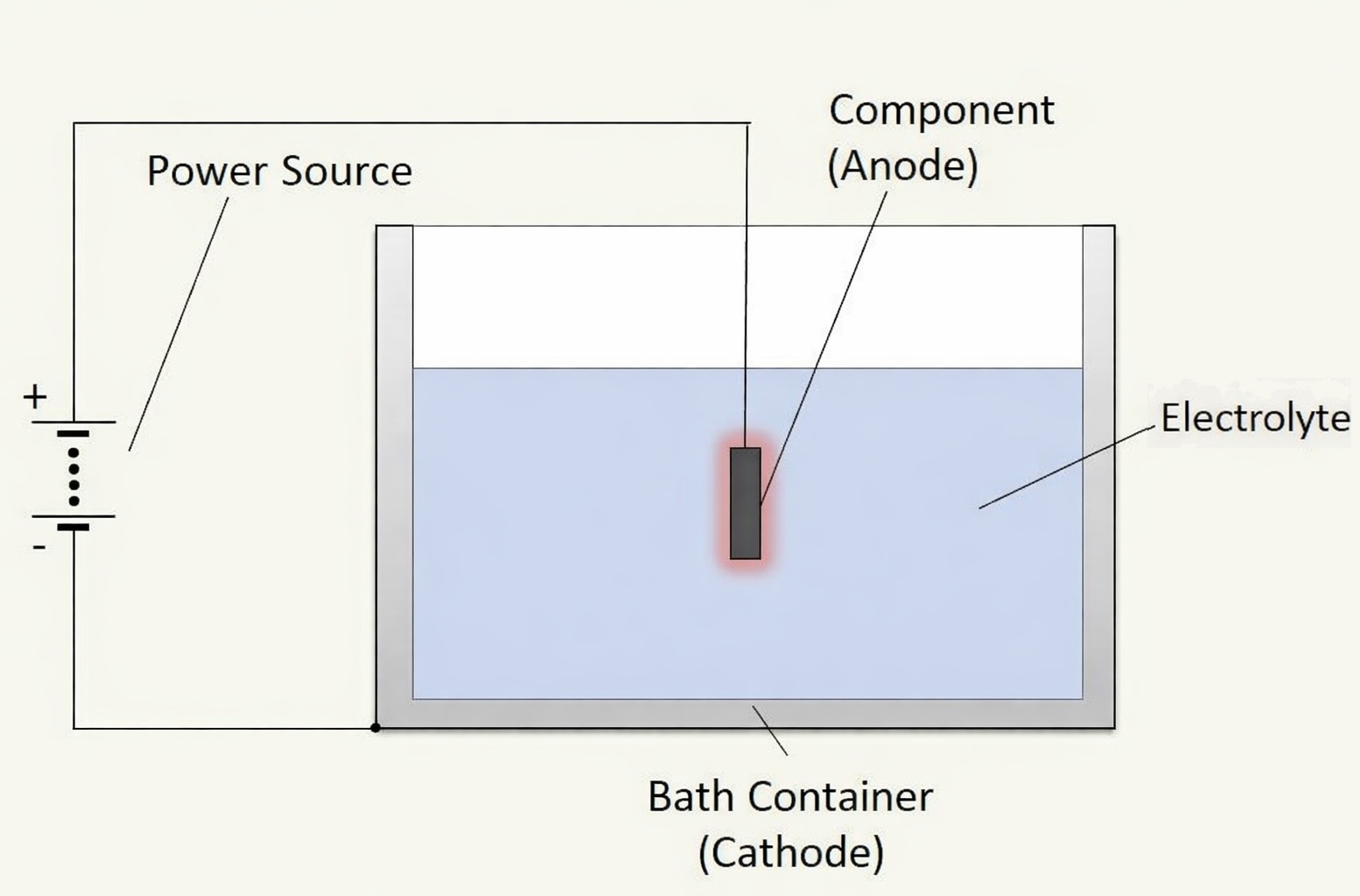

Electrically conductive connections between the poles of the DC source and two spatially separated metal objects turn these objects into electrodes. The electrode connected to the negative pole is called the cathode, while the one connected to the positive pole is the anode. In anodic oxidation, the anode is the workpiece that is to receive an oxide layer. To build this layer, an electrolyte is required that surrounds the anode and at least wets the cathode.

Electrolyte

The electrolyte for anodizing consists of bases (alkalis), acids, or salts dissolved in water. These substances consist of electrically positive and negative ions. In water, the ions are separated and freely mobile. At first glance, it seems as if the electrolyte could conduct electricity. On closer inspection, however, the ions migrate to the electrode with the opposite electrical charge, where they accept or release electrons. In doing so, the ions equalize their own charge and undergo chemical transformation.

Chemical Reactions

In chemistry, reactions in which electrons are accepted are called reductions. These reactions occur at the cathode, where there is an excess of electrons. During anodizing, hydrogen gas is typically formed at this electrode.

At the anode, where electrons are lacking, ions release electrons. This process is known as oxidation. In anodizing, oxygen acts as the electron acceptor and bonds with the electrode material to form a metal oxide.

What Exactly Is Anodizing? Process Sequence of Anodizing

Pretreatment as a Prerequisite for Defect-Free Layer Formation

A uniform oxide layer can only form on metallically clean surfaces. Thorough surface pretreatment is therefore essential. Surface technology provides mechanical and chemical methods that remove all types of contamination from materials.

Mechanical surface treatments remove stubborn contaminants and corrosion products. They also create a defined surface structure—such as glossy or matte—and can eliminate scratches or defects. Mechanical pretreatment typically involves brushing, blasting, grinding, or polishing.

Chemical pretreatment primarily removes contamination from previous process steps, such as oils and greases used as corrosion protection or cooling and forming lubricants from manufacturing. Common steps include alkaline degreasing and pickling in acidic or alkaline baths to remove remaining contaminants and natural oxide films.

Sequence of Anodizing

Individual workpieces are mounted on racks and immersed in the electrolyte bath. Alternatively, sheet metal wound into coils can be drawn through the bath and rewound after anodizing. A conductive connection to the positive pole of the DC source ensures that the workpiece becomes the anode. The container material often serves as the cathode; if that is not possible, cathodes are mounted on the side walls of the tank and connected to the negative pole.

Once the power source is switched on, the ions begin to migrate. Initially, a thin, electrically insulating metal oxide layer forms on the workpiece or semi-finished product. Because the anode continues to attract negative ions, these ions accumulate in front of the layer. The voltage rises until it reaches a value that allows the ions to penetrate the layer and reach the base metal to form new metal oxide. This process often produces visible sparks. Oxidation continues at the base metal, forming a porous layer with countless microscopic channels. The structure of the oxide layer can be varied widely by adjusting the electrolyte composition, current intensity, and temperature.

Post-Treatment to Seal Pores and Add Color

The porous structure of the fresh metal oxide layer is ideal for absorbing dyes. However, if you choose to dye the freshly formed metal oxide layer, the pores must be sealed. This step is usually performed in a hot-water bath. At 208.6 °F (97 °C), the metal oxide reacts with water (hydration). This increases the volume of the layer and compresses the pores. This densification process is known as sealing. As an alternative, surface technology also offers pore filling using waxes.

Applications of Anodizing

Anodizing is well suited for producing corrosion- and wear-resistant oxide layers on light metals. This is primarily due to the properties of the oxides. The process is primarily used for aluminum, titanium, and magnesium. Attempting to anodize stainless steel would fail because its corrosion protection is provided by a very thin oxide film formed by chromium in the alloy reacting with oxygen in the air.

Anodizing Aluminum

Anodizing aluminum is the most widespread and best-studied variant of anodizing. It has acquired its own name: *Eloxal*. Aluminum is used in aerospace, automotive engineering, machinery, equipment manufacturing, construction, and architecture.

Anodizing Titanium

Titanium is an ideal material for aerospace and aviation due to its low density, high mechanical strength, and excellent heat resistance. These properties, combined with outstanding chemical resistance, make anodized titanium valuable for the chemical industry and medical technology.

Anodizing Magnesium

Because magnesium is extremely lightweight yet strong, it is gaining interest in the automotive and equipment manufacturing sectors. However, anodizing magnesium is challenging due to its high reactivity. It requires special approaches both in preparation and during anodic oxidation.

Kluthe Magazine

Kluthe Magazine