Emulsifiers ensure that all components of water-miscible metalworking fluids remain evenly distributed in the liquid during use. This is the only way to fully benefit from the friction-reducing properties of oils and the excellent cooling performance of water, allowing both to be used effectively for metal cutting and forming. Learn more about how emulsifiers work in metalworking fluids.

What Are Emulsifiers?

Emulsifiers are included in the broader class of surfactants. These are chemical substances with a special molecular structure. Their molecules consist of a water-attracting (hydrophilic) end and an oil-attracting (lipophilic) end. The ratio between these two parts determines whether a surfactant is more soluble in water or in oil. This molecular structure causes the molecules to migrate to interfaces and align toward the phase they favor. An interface can be, for example, the surface of a liquid where it is exposed to the surrounding air.

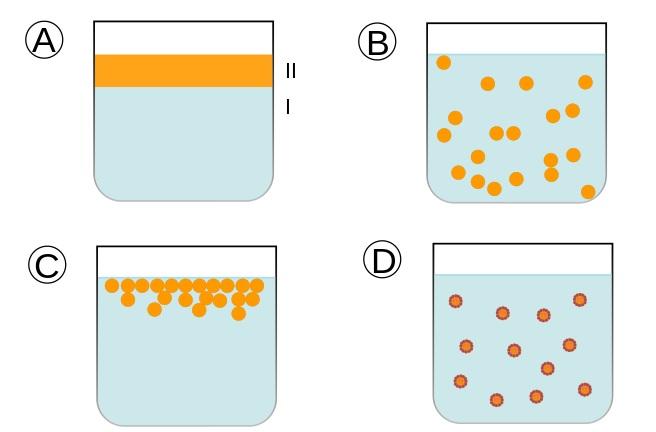

Interfaces also occur between liquids that do not mix. The heavier liquid collects at the bottom (sedimentation), while the lighter liquid rises to the top (creaming). When surfactants are present in the mixture, they occupy the surface that separates the two phases. If the two phases are mixed by vigorous shaking or stirring, droplets form. The surface of a droplet represents another interface where surfactants accumulate. If this process results in a stable mixture, it is called an emulsion. In such a system, the surfactants function as emulsifiers.

A) Two immiscible liquids, not yet emulsified

B) A (temporary) emulsion of the two liquids

C) The unstable emulsion gradually separates

D) Only the surfactant (outline around the particles) ensures a stable emulsion

Requirements for Emulsifiers in Water-Miscible Metalworking Fluids

Chemical Stability of the Emulsifiers

Water-miscible metalworking fluids are concentrates whose main components are base oils. These oils act as lubricants. To ensure the lubricants disperse in water, the concentrates contain emulsifiers. In addition, the concentrates include various additives that further stabilize the emulsion, protect the materials against corrosion, inhibit microbial growth, and prevent excessive foam formation. Each component must retain its properties during storage and use. Only then can they perform their specific functions in the metalworking fluid. This requires that the components do not form chemical bonds either with one another or with water.

Adapting Emulsifiers to Water Hardness

Water-miscible metalworking fluids are emulsions composed of concentrates and water. For mixing, ordinary tap water is typically used, which always contains a certain amount of dissolved minerals—primarily magnesium salts, calcium salts, and carbonates. The amount of dissolved minerals determines the water hardness, expressed in degrees of German hardness (°dH), which roughly corresponds to grains per gallon (gpg).

If the hardness is below 5 °dH, the emulsions tend to foam excessively. If it exceeds 20 °dH, water-insoluble lime soaps may form and deposit on the surfaces of tools and workpieces. Choosing suitable emulsifiers for metalworking fluids can reduce these issues to some extent. However, it is generally more effective to adjust the water hardness itself—either by diluting the water with deionized water or by increasing the hardness with appropriate salts—to bring it into the optimal range.

Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balance

The hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) is a scale used to classify surfactants according to their areas of application. Values range from 0 to 20, where 0 represents a completely oil-soluble, water-repelling substance and 20 represents a completely water-soluble, oil-repelling substance. Between these extremes, surfactants are arranged according to their solubility. The oil-to-water ratio in the emulsion determines the choice of suitable emulsifiers. In most cases, one component predominates (the continuous phase), while the other is dispersed within it in droplet form (the dispersed phase). Water-based metalworking fluids usually contain 5–10% concentrate, making water the continuous phase. For a stable metalworking fluid, emulsifiers are required that are equally or slightly more soluble in water than in oil. Their HLB values typically range between 8 and 18. The optimal emulsifier depends on which lubricants and other additives are included in the formulation of the metalworking fluid.

| HLB Value | Application | Miscibility with H2O |

|---|---|---|

| 1.5 to 3 | Defoamers | Insoluble |

| 3 to 8 | for W/O emulsions | Milky when stirred |

| 7 to 9 | Wetting agents | |

| 8 to 18 | for O/W emulsions | Stable (milky) emulsion |

| 13 to 15 | Detergents | Clear emulsion / clear solution |

| 12 to 18 | Solubilizers | Clear emulsion / clear solution |

Influence of Droplet Size

Emulsion stability also depends on the droplet size within the dispersed phase. The smaller the diameter, the more stable the mixture. However, producing very small droplets requires significant effort. On the one hand, a large amount of mechanical energy is needed to continually reduce the droplet size. On the other hand, the total surface area increases, leading to higher consumption of emulsifiers. It should also be considered that an equilibrium forms between emulsifier molecules adsorbed onto the dispersed phase and those dissolved in the continuous phase. Consequently, more emulsifier is required than the droplet surfaces can actually accommodate.

Production of Metalworking Fluid Emulsions

Most metalworking fluids belong to the category of coarse-dispersed macroemulsions with droplet diameters greater than 1 µm (1 micrometer or 0.00004 in). Mixing is often performed with adjustable dosing devices connected to a freshwater line. The core component of these devices is a Venturi nozzle. The free diameter of this nozzle narrows down to a throat and then widens again. Because the flow velocity of the water is very high at the narrowest point, the pressure drops significantly (according to Bernoulli’s principle). This pressure drop is sufficient to draw in the metalworking concentrate through a hose connected to the throat. As the concentrate is entrained by the flow, an emulsion with the desired droplet size distribution is formed.

Another common method is to add a metered amount of water to a container and then add the required quantity of concentrate. The liquids are first mixed slowly. Adequately small droplets can then be produced with the aid of a stirrer.

Kluthe Magazine

Kluthe Magazine